What Is LTV and How It Drives Startup Growth and Valuation?

By Lior Ronen | Founder, Finro Financial Consulting

Customer Lifetime Value (LTV) tells you how much revenue a single customer generates over the time they stay with your product. It looks beyond the first transaction and measures the long-term value of a relationship, not just a sale.

A startup with strong LTV can afford to invest more in growth, recover acquisition costs faster, and generate profit that compounds over time.

Two companies can have the same revenue, but the one with higher LTV will always be more valuable. High LTV signals strong retention, pricing power, product stickiness, and customer loyalty—all signs of a defensible business.

Low LTV means you are constantly replacing customers, burning cash to stand still, and leaving money on the table.

In this article, we’ll break down what LTV really means, how to calculate it in a meaningful way, why investors care about it more than top-line revenue, and how improving LTV can transform your financial model, growth strategy, and valuation.

High LTV and efficient CAC determine whether growth creates lasting value or burns cash. When customers stay longer, expand usage, and generate strong margins, each new user becomes more profitable over time. As the business matures, LTV should rise while CAC stabilizes or declines, widening unit economics and compounding growth. The LTV:CAC ratio reveals if growth is scalable, capital-efficient, and attractive to investors. Founders who design retention, pricing, expansion, and acquisition intentionally build models that get stronger with scale—and create companies that are durable, fundable, and highly valuable.

What Is LTV (Customer Lifetime Value)?

LTV measures the total revenue a customer generates over the full time they stay with your product.

It moves beyond the first transaction and captures the long-term value of a relationship, not just a single sale. A high LTV means customers stick around, spend more, and become more valuable over time.

Basic LTV formula:

LTV = Average revenue per customer × Average customer lifespan

If your average customer pays $100 per month and stays for 12 months, LTV is $1,200.

However, revenue alone does not tell the full story.

Why LTV should be based on gross margin, not revenue

Revenue shows how much a customer pays you.

Gross margin shows how much you actually keep after delivering the product.

If you collect $200 but spend $120 on hosting, support, or infrastructure, that customer is not worth $200—they are worth $80. Founders who calculate LTV using revenue overestimate the health of their business. Calculating LTV using gross margin reveals true unit economics and profitability.

Real-life example: AI SaaS startup in 2025

Average subscription price: $200 per month

Average gross margin: 80%

Average customer lifespan: 18 months

Expansion revenue per customer: +$50 per month after month 6

Step 1: Monthly gross profit

$200 × 80% = $160

Step 2: Expansion revenue after month 6

($200 + $50) × 80% = $200

Step 3: Lifetime value

First 6 months: $160 × 6 = $960

Next 12 months: $200 × 12 = $2,400

Total LTV = $960 + $2,400 = $3,360

If the founder used a simple revenue formula ($200 × 18 = $3,600), they would overestimate LTV and ignore the cost of serving customers. The accurate LTV ($3,360) reflects real profit and includes expansion, retention, and gross margin.

LTV is not a guess. It is a reflection of actual customer behavior—how long they stay, how much they pay, and how much value they create over time. Done correctly, LTV reveals whether growth compounds or collapses.

Why LTV Matters?

LTV tells you the quality of your growth, not just the size of it.

A startup with a high LTV customer base can afford to spend more on acquisition, recover costs faster, and generate profit that compounds over time.

A startup with low LTV must constantly replace churned customers, burn cash to keep revenue flat, and struggles to scale.

LTV reflects retention, pricing power, product stickiness, and customer loyalty, four things investors care about more than short-term revenue.

When LTV is strong, every new customer becomes more valuable the longer they stay. When LTV is weak, every new customer becomes a liability.

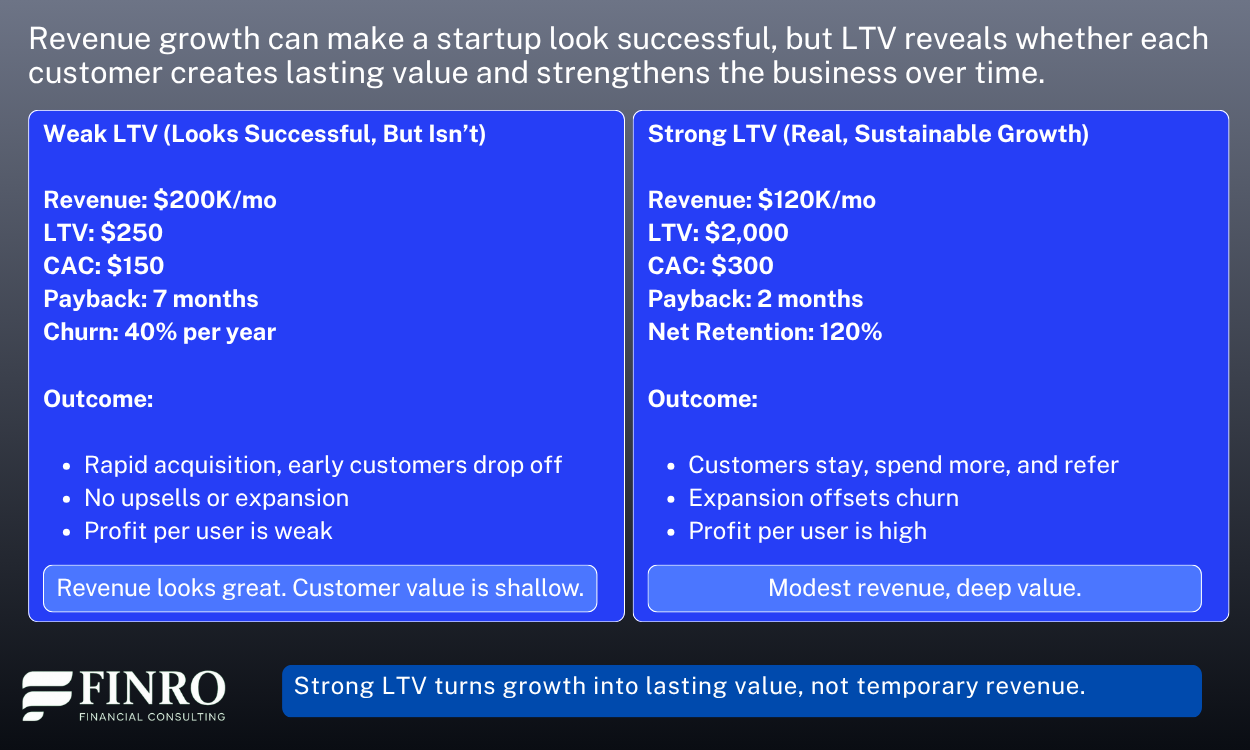

Two startups can have the same revenue and completely different futures:

Example 1: High Revenue, Low LTV → Fragile Business

A consumer app grows from $0 to $300K in monthly revenue with aggressive paid acquisition. But users leave within two months, pricing is low, and there is no expansion revenue.

LTV: $80

CAC: $50

Payback: 1.6 months

Churn: 50% every 60 days

Result: Growth stalls, retention collapses, CAC eventually rises, and burn rate explodes.

Outcome: The business looks big but has no depth. Revenue is high, but value is low. Investors lose confidence.

Example 2: Lower Revenue, High LTV → Scalable and Valuable

An AI SaaS tool grows slower, reaching $150K in monthly revenue. Customers stay 18+ months, upgrade to higher tiers, and refer new users.

LTV: $3,000

CAC: $400

Payback: 2 months

Net Revenue Retention: 120%

Result: Each customer becomes more profitable over time and drives organic growth.

Outcome: The business compounds value with every customer. LTV fuels scale, improves margins, and attracts top-tier investors.

LTV is the difference between chasing growth and building a durable company. It shows whether your revenue is fragile or compounding, and whether your business model gets stronger or weaker as you scale.

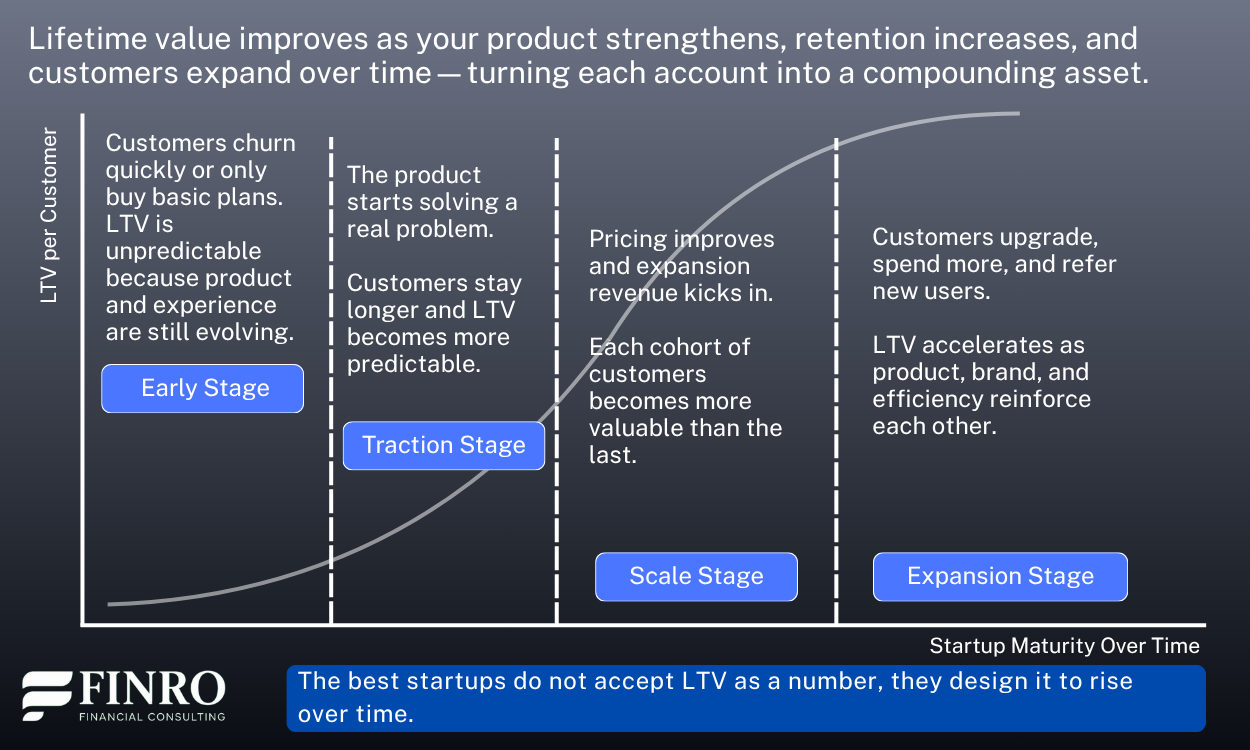

LTV Is Not Static, It Changes as Your Startup Evolves

Most founders treat LTV like a fixed number in a spreadsheet. In reality, lifetime value is dynamic. It rises or falls based on product quality, retention, pricing power, expansion revenue, and customer experience.

In the early stage, LTV is usually low and inconsistent because customers churn quickly or only buy the basic plan. As the business matures, retention improves, upsells increase, and gross margin expands — pushing LTV higher.

The best startups don’t accept LTV as a result. They actively engineer it over time by improving onboarding, launching higher-value plans, strengthening retention, and reducing delivery costs. When done well, each new customer becomes more profitable than the one before.

Two companies can start with the same revenue and CAC but end up very different:

Example 1: LTV declines over time (bad sign)

A one-size-fits-all product launches fast and acquires early users. But churn increases, there is no expansion path, and delivery costs remain high.

Year 1 LTV: $1,200

Year 2 LTV: $900

Year 3 LTV: $600

Result: Each new customer becomes less valuable. Growth requires constant reacquisition. Eventually, the model breaks.

Example 2: LTV increases over time (great sign)

A SaaS startup improves onboarding, launches new features, adds usage-based pricing, and invests in customer success. Customers stay longer and spend more.

Year 1 LTV: $800

Year 2 LTV: $1,500

Year 3 LTV: $2,400

Result: Each new customer becomes more profitable than the last. Growth compounds. Investors love this.

LTV is not just a formula, it is a reflection of how well your business improves over time. If LTV goes down, your model is eroding. If LTV goes up, your business is getting exponentially stronger.

LTV in Your Financial Model

Most founders treat LTV as a vanity metric on a slide. In a real financial model, LTV is the output of how well your business retains customers, expands revenue, and generates margin over time.

You don’t plug in an LTV number — you build the drivers that create it.

A credible model shows:

How long customers stay (retention / churn assumptions)

How much they spend over time (pricing + expansion)

How much profit you keep (gross margin)

How LTV compares to CAC (profitability of growth)

How LTV improves as the business matures

When these drivers are built into the model, LTV becomes a strategic lens, not just a calculation. It shows how value compounds over time and whether each new customer makes the company stronger or weaker.

This is exactly what investors analyze in your model:

Does retention improve over time?

Do customers upgrade or expand?

Do margins get better as you scale?

Does LTV/CAC improve, or does it fall apart?

If LTV rises while CAC stabilizes or declines, your model tells a powerful story: each new customer creates more value than the one before.

That is the difference between linear growth and compounding growth — and it’s the difference between a good startup and a great one.

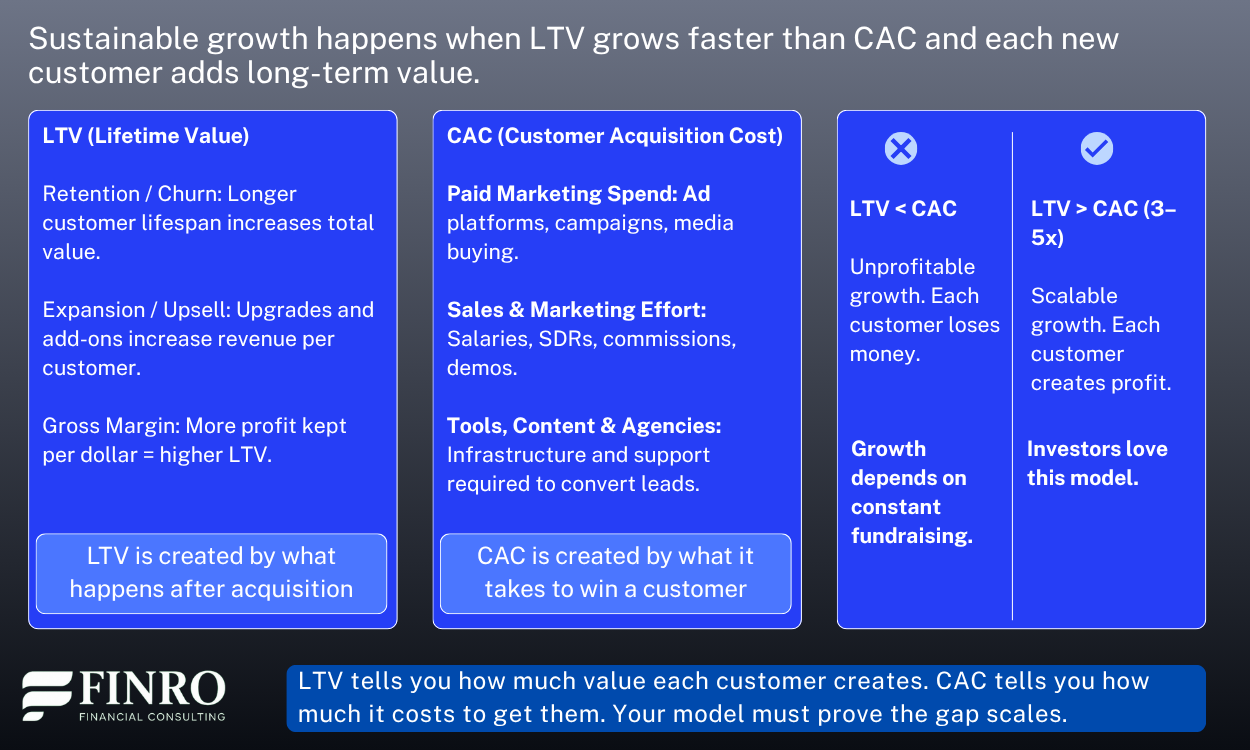

The LTV:CAC Ratio Is the Real Signal of Growth Quality

LTV and CAC on their own only tell half the story. The true test of a scalable business is how much value each customer creates compared to how much it costs to acquire them. This is why investors look at the LTV:CAC ratio before anything else — it instantly reveals the quality, profitability, and efficiency of your growth.

A healthy ratio (typically 3–5x) means every $1 spent to acquire a customer generates $3 to $5 in lifetime value. That gives you room for profit, reinvestment, and compounding growth. A weak ratio (1–2x) means you’re barely breaking even. Anything below 1x means you lose money on every customer and must rely on fundraising to survive.

The power of the ratio is not just in where it is today — it’s in where it’s going. If your model shows LTV rising and CAC holding steady or declining, your business gets stronger with scale. If LTV falls or CAC rises over time, your model collapses no matter how fast revenue grows.

Investors don’t fund growth alone. They fund efficient growth. And the LTV:CAC ratio is the simplest way to prove that each new customer makes your company more valuable than the one before.

Summary

LTV is not just a formula — it reflects retention, pricing power, product value, and customer loyalty. When LTV increases over time, each customer becomes more profitable, margins improve, and growth compounds. When LTV consistently exceeds CAC, your model proves capital efficiency and scalability, which is exactly what investors want to fund.

The strongest startups don’t guess LTV — they design it through better onboarding, deeper engagement, expansion revenue, and operational excellence. They don’t just acquire customers. They maximize the value of each one and turn growth into long-term enterprise value.

This is what we build at Finro.

We don’t just model numbers. We design LTV and CAC engines that scale, improve over time, and give you the confidence and credibility to raise capital, deploy it wisely, and grow with control.

Key Takeaways

LTV reflects retention, pricing power, expansion revenue, and gross margin, revealing how valuable each customer becomes over time.

A startup with high LTV can afford stronger acquisition, scale profitably, extend runway, and attract higher investor confidence.

LTV is not fixed; it rises or falls based on product quality, customer experience, pricing strategy, and operational efficiency.

When LTV consistently exceeds CAC with a healthy ratio, growth compounds and each new customer strengthens the business.

Founders who design and model LTV intentionally build scalable unit economics, credible financial forecasts, and higher company valuation.

Answers to The Most Asked Questions

-

A “good” LTV depends on pricing and model, but strong startups aim for LTV at least 3–5 times CAC with healthy retention.

-

Revenue shows how many customers you have. LTV shows how valuable each customer is over time, which drives profitability, retention, and valuation.

-

Use gross profit per customer, multiply by average lifespan, and include expansion revenue. LTV must reflect real retention and margin, not just price.

-

Improve retention, launch higher-tier plans, add usage-based pricing or expansions, increase product adoption, and boost gross margin to capture more profit.

-

LTV proves customers stay, spend more, and create profit over time. High LTV signals product-market fit, defensibility, and scalable growth—key drivers of valuation.